Rahiminia tells me that this video was shot on Newroz, the Kurdish new year, and that while the mirrored faces and voices are tethered by shared celebrations of fire, song, and stories, the video quietly insists on a bitter truth: these celebrations will unfold apart, carried out in separation, divided by borders.

Watching alongside Rahiminia, it becomes evident that these visuals mark the epicentre of his artistic practice. Borders form both the texture of his childhood, and the conceptual core from which his art unfolds. Born in 1986 in Marivan, a Kurdish city in Iran, just a few kilometres from the Iraq-Iran border, Rahiminia grew up with the reality of separation etched into daily life. The lines that carve through Kurdistan are the long aftershocks of the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, when French and British powers partitioned the Middle East into the emerging nation-states of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Overnight, the Kurdish people were fractured into minorities — casualties of colonial cartography.

What began as an external act of imperial design soon seeped inwards, embedding itself within the architectures of power of these new states. Kurdistan was, and crucially still is, undergoing ‘internal colonisation’, with colonial power relations perpetuated within the internal structures of the four nation-states. Denialist and assimilationist policies have persisted through projects of epistemic erasure, enforced by systems of law, education, and surveillance. For Kurds especially, there’s no such thing as the ‘postcolonial’.

And yet, Rahiminia’s art does not linger in the shadow of loss. It turns instead towards presence; towards the endurance of culture, the persistence of memory, and gestures of resilience that cross fences even when bodies cannot. In his hands, identity does not dissolve at the line of division but travels across it, gathering new shapes as it moves. Rahiminia asks what it means to traverse these thresholds; how an ethnicity can endure division and remain whole.

To me, his work draws from the enduring spirit that, in the Kurdish consciousness and language we both inherited, has long refused the permanence of imposed borders. The land continues to be imagined through its own geography: Bakur (North Kurdistan/Turkey), Başûr (South Kurdistan/Iraq), Rojava (West Kurdistan/Syria), and Rojhilat (East Kurdistan/Iran). Rahiminia’s practice contemplates the enduring weight of ‘internal colonialism’, tracing its generational effects, while affirming the persistence of Kurdish identity. His works are active.

Rahiminia tells me with stark clarity who he is: a Kurdish artist. For him, the distinction is not semantic but existential. Statelessness has already made the task of gaining recognition on these terms fraught: in international exhibitions and biennales, Kurdish artists are rarely acknowledged under the rubric of ‘Kurdish Art’. Usually, they appear under the national labels of the states in which they reside (Turkey, Iran, Iraq, or Syria), subsumed into categories that obscure the specificity of Kurdish experience. This structural absence makes clear that the curatorial, like the Kurdish question, is bound to the politics of visibility and erasure.

Rahiminia undertakes this task in his newest and ongoing body of work, Borders (2025-). The spine of the series is the installation Border No.1 (2025): two wooden posts spun by a taut chain-link fence, crowned with coils of barbed wire, cite the brutal architecture situated across the internal edges of Kurdistan. From this piece, subsequent works begin to grow flesh — Border No.2, Situation 1 (2025), Border No.2, Situation 2 (2025), and Border No.2, Situation 3 (2025) all extend like evolving organs, producing threads across varying mediums which trace Rahiminia’s devotion to voicing the fractures of bordered-division.

It is Border No.1 (2025) that also anchors the series: a stark emblem of oppressive architecture, appearing as if uprooted from a landscape of control and transplanted into the unfamiliar stillness of the gallery. As the first work in the series, it serves as a conceptual blueprint, establishing the visual and structural language from which the later installations evolve. Shortened in width, the fence is stripped of its utility, no longer able to prevent movement, and becomes instead an object of contemplation rather than coercion. Reconfigured into a sculptural form that can be circled and scrutinised from every angle, this displacement exposes the border’s architecture of colonialism at its barest, transforming it into a site of uneasy reflection. In doing so, the gallery becomes contested terrain, where audiences confront the paradox of engaging aesthetically with a structure that, beyond its walls, enacts deep political violence.

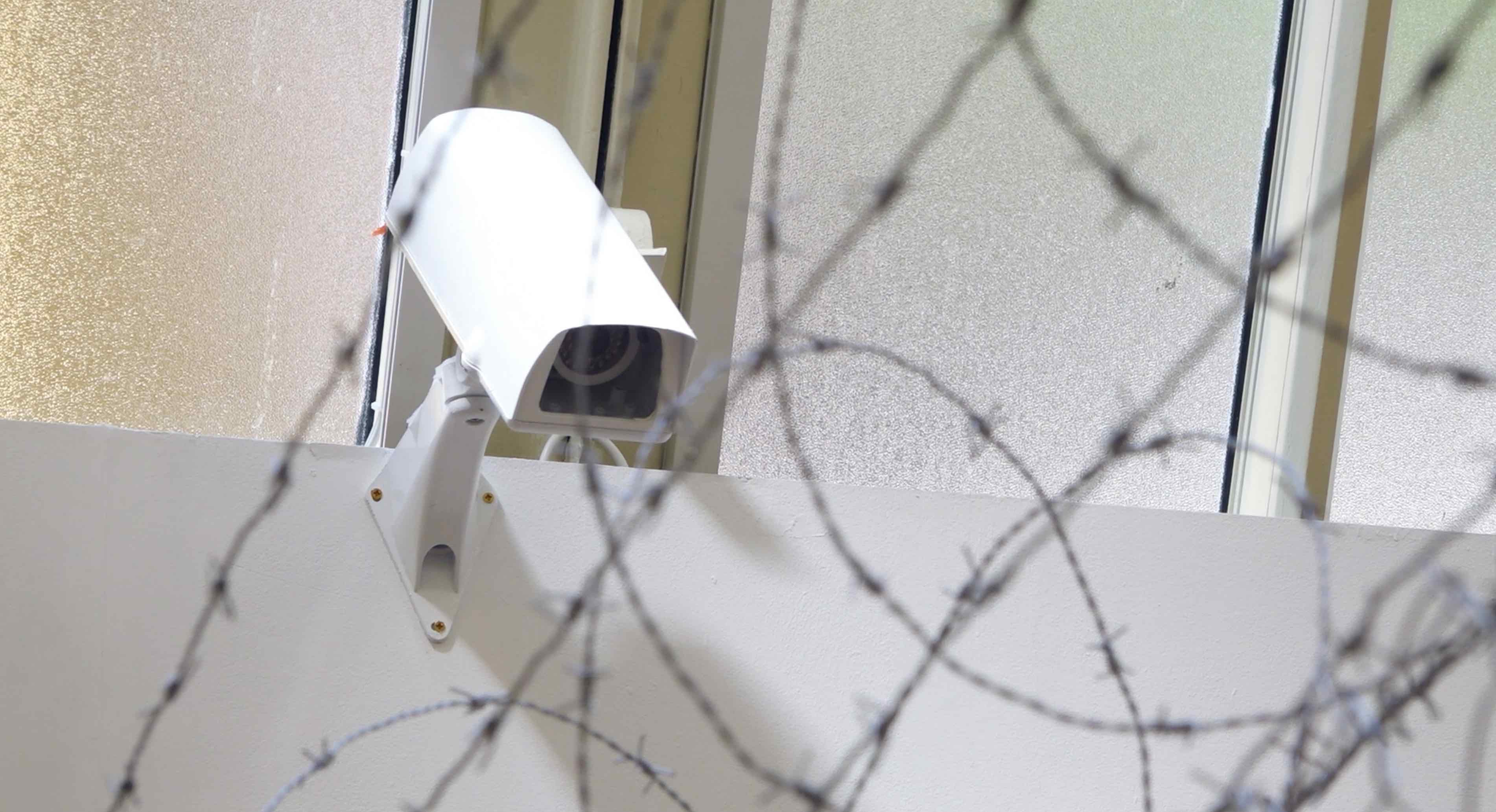

Out of this, Border No.2, Situation. 1 (2025) emerges. The sculpture contains four CCTV cameras, two on each side, equipped with face detection technology, registering the faces that dare approach the border. In adding cameras, and having the images they capture displayed live on a screen in the gallery, Rahiminia’s installation undermines the sanitised safety of the gallery space, plunging viewers into the militarised operative reality of border crossings. We are stripped of context needed to place this as a specific border, the work carrying instead a bleak universality. The fence could stand for countless checkpoints, or detention zones. It’s hard not to read the exposed structure as echoing the escalating border regimes of our present — most pointedly, my present, and the UK’s current policies of deterrence and offshoring, where the cold language of migration, asylum, and security is increasingly bound up with criminalisation and dehumanisation. In this way, the language of Rahiminia’s work, while rooted in the Kurdish experience of division and displacement, speaks urgently to border politics everywhere.

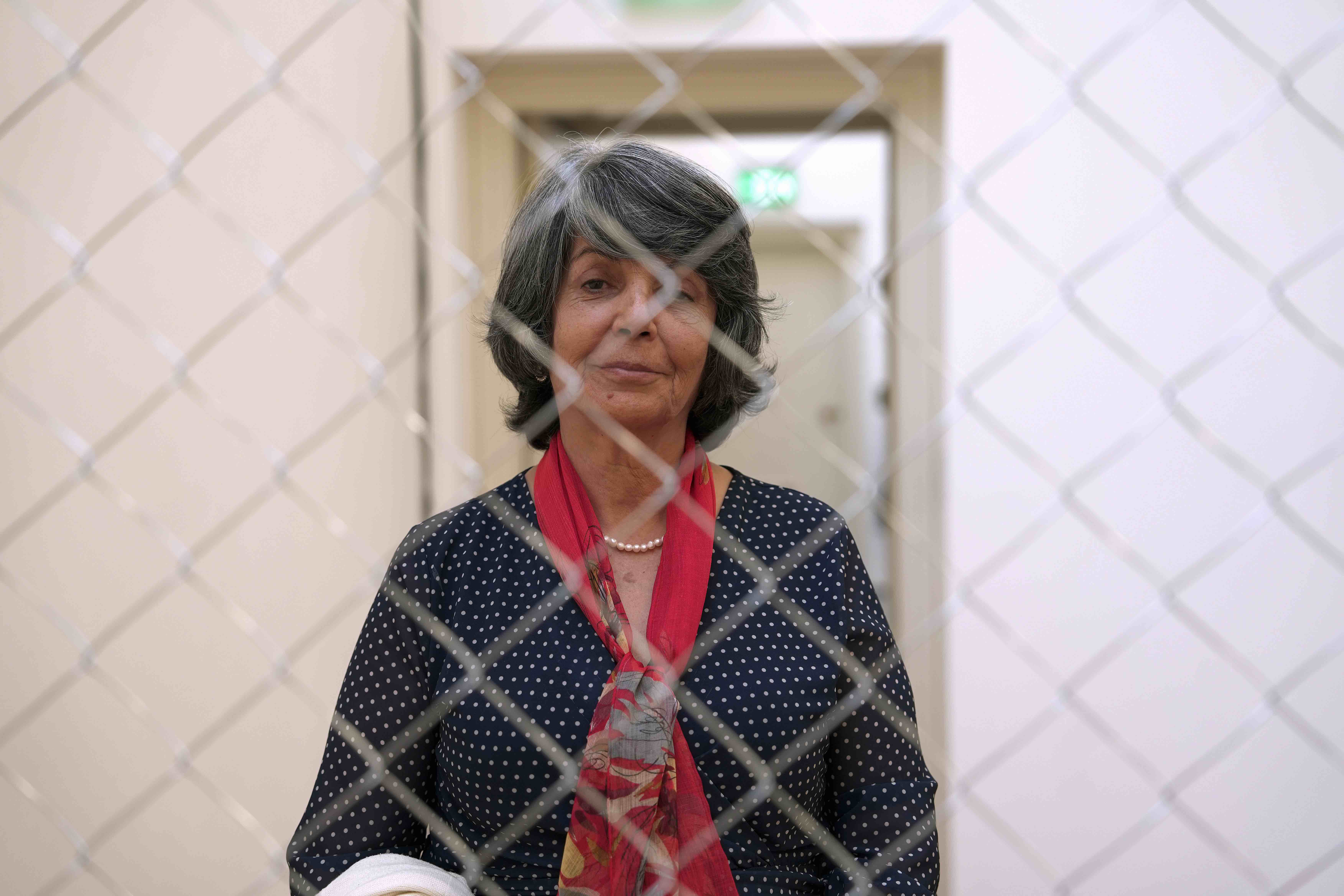

In contrast, in Border No.2, Situation. 2 (2025) the cold universality of the fence collapses into scenes of personal rupture, where the abstract violence of division acquires a human pulse. The installation is developed through the use of performance, staging participant families as dispersed across the divide, each confined to their section. Mechanisms of surveillance and control are mirrored in the gallery space as CCTV footage records movement on either side of the fence, recording lived fractures cutting across familial ties. Border No. 2 is therefore not only a critique of territorial obstruction, but also of the way borders reconfigure human relationships. The presence of living bodies transforms the border from an object to an encounter; separations are no longer symbolic but felt, spoken, and inhabited. Rahiminia’s representation of bordered separation is distinguished by the way it physically translates geopolitical violence into the realm of the everyday. And while it still resists being tied to a single geography, Border No.2, Situation. 2'’s biographical weight is unmistakable, echoing both Rahiminia’s, and the wider Kurdish experience, of separation and enforced estrangement.

In Border No.2, Situation. 3 (2025), any ambiguity as to which border is being represented is overridden. Threaded through the fence is a speaker wire, an umbilical line stretching across the divide, carrying with it the signal of old Kurdish songs. From a speaker on the opposite side, fragments of melodies once passed hand-to-hand as contraband are playing, reanimated within the white walls of the Royal Academy studio. For Kurds, these restrictions extend beyond just territory, but into the realms of cultural expression itself. For Rahiminia, borders did not only cut across land, they criminalised culture. In this act of transmission, his work evokes that deeper wound of ‘internal colonisation’, where even music must trespass to be heard.

Music reels, cassettes, videos, even the recordings of dengbêj (Kurdish sung stories) consequently became illicit cargo, smuggled through mountain paths and hidden beneath clothing. To carry a song was to risk punishment; to listen was to resist erasure. Kurdish culture survived not in spite of illegality, but through it. In Border No. 2, Situation. 3 Rahiminia pays homage to this survival. The fence’s wire is no longer only a barrier but a conduit, a dynamic transmission of sound across the divide, inviting viewers to recognise identity as often finding ways to echo across violently imposed borders and checkpoints.

Argentine postcolonial theorist Walter Mignolo’s claim that ‘border thinking requires dwelling at the border’ is resonant in Rahiminia’s work.1 By not dismissing borders as only lines of control, but also as spaces where culture, memory, and solidarity persist, Border No. 2, Situation. 3’s metal threads and melodies trace the border’s violence, while also revealing its capacity to connect. Placed alongside his wider work, we find a catalogue of counter-archival approaches that seek to preserve Kurdish memory, identity, and culture.

To me, Rahiminia’s practice ultimately confronts the long history, and present, of epistemic violence that seeks to overwrite Kurdish memory. In this sense it is explicitly anti-colonial. His work insists on culture as resistance, creating forms of knowledge that, through subjective and visual dialogues, installations, portraits, and assemblages, generates ways of knowing that are both affective and political. He asks how Kurdish identity can remain alive today under conditions where coloniality is not an afterlife but a continuing reality. Central to this is the question of borders: not only as territorial lines, but as forces that have defined and constrained both my own individual identity, and the collective identity of Kurds everywhere. Rahiminia’s Borders series exposes the violent architecture which facilitates this.

By ‘dwelling at the border’, Rahiminia confronts the structures embedded in collective Kurdish consciousness, an art that does not simply represent survival but illuminates the ways we, as Kurds, have learned to remember and resist.

Heja Rahiminia (b. 1986) is a multidisciplinary artist whose work spans photography, video, sculpture, and installation. Through his practice, he examines themes of identity, war, displacement, borders, and colonialism, informed by his lived experience of the social and political realities of his homeland.

1. Weier, Sebastian, ‘Interview with Walter D. Mignolo’ in E-International Relations, (2017).

Images // Work

1. Border No.1 (2025) 2.8x2m installed at the Royal Academy, Courtesy of the artist

2-3. Border No.2, Situation 1 installed in the Keeper’s Room, Royal Academy (2025), Courtesy of the artist

4-7. Border No.2, Situation 2 installed in the Keeper’s Room, Royal Academy (2025), Courtesy of the artist

8. Border No.2, Situation 3 installed in the Keeper’s Room, Royal Academy (2025), Courtesy of the artist