Lu Rose Cunningham:

|

To begin with, what is it about sound and voice that moves you, that propels you to want to make? How does your interest in sound and voice influence your choice of materials? |

|

Isabelle Pead:

|

Singing and the sonic has always been an intrinsic, woven part of my life, and in the last five to seven years it really cemented itself in my art practice as the central ethos of everything that I was building, built around voice, and in particular built around my voice. I was really drawn to sound for how pervasive it is, and it’s a medium which is constantly in flux. It speaks of the ‘interior’ and ‘exterior’ [of space, of the body]. It’s deeply personal but also projected, it’s transitional and migratory, it comes from within us and moves into other people. It’s penetrative in that way. And it has a power and scope, for greatness, or something greater, or beyond, something transcendent. I grew up singing oratorio, which is really big church music in these spaces which are designed to amplify sound, and to create it you think about the higher power that you’re pointed towards; it moves you in a way which is quite ineffable. Sound is always the thing I sit with and come back to, and then I find materials which sit within that and reflect that. So everything that’s sculptural is sonic-sculptural; it always sits within a resonance and a sounding. It’s one of the reasons that I really like metal — it holds this total antithesis to sound, but also is this amazing companion. It’s reflective, it vibrates and it moves with sound. But there’s a sterility to it too, which really opposes this fleshy, organic voice and I love that these two reflect and reverberate with each other. Similarly it’s why I really like using synthesised sound — that to me is almost the midpoint, the crossing, where you have organic voice on one end of the spectrum and you have metal, the inorganic, on the other side, and in the middle you have synthesis which is this amazing merging of the two. |

|

Lu:

|

You have mentioned to me before that your work centres on the relationship between the voice and the sounding body, and considers softness, utterance and the in-between. Softness, utterance and the in-between — which are very sensorial, and sensual words — what do you mean by these, for you and in the context of your practice? |

|

Isabelle:

|

I’m finally giving in to the fact that the sound that I sit with and produce, and am interested in, is all about emotion, and even if it’s not a prescribed emotion by me, it has an emotional effect on other people, whether that is one of awe, grief or mourning, joy or ecstasy. All of these things can be amplified by the sonic and the spaces that reflect it [back]. The sound is of me and therefore I am intrinsic to my work, and me as a human and my personality sits within that, as does my emotion — my love, my grief, my loss. Seeing the Ed Atkins show recently at Tate Britain really made me think about how the artist can sit quietly but so deeply, personally and vulnerably within the work. And then also there is this care, sensuality, softness — all of these things come from the organic voice I mentioned, the fragility, frailty and mess ups that happen in my voice. I try to lean into that and explore it; that’s why I’m not making traditional scored operatic work. I make contemporary sound, which has elements of traditional opera but reflects all of the fragility of this voice and messiness; it’s an imperfect voice, and it’s a voice of care. A voice that needs to be held but also holds other people. |

|

Lu:

|

That’s beautiful. Thinking about the emotional effect on others and the role of the listener — them engaging with the work and by extension you — how do you feel about that, when you’re making or sounding, recorded or live? Does the listener/observer/participant play into that, or inform in time the work? |

|

Isabelle:

|

It really informs post [performance] — I think so much about the architecture of the space for performance, and then the audience I think I often let that go; I can sit with my intention for the works but I don’t know if I will ever have power to influence the emotion that comes from it, that impacts upon other people. So with the takeaway for the audience, I can start with my intentions for the work but I don’t want to be dictatorial, so that there can be a wonderful range of emotions in response to it from people. I think that’s really special, even if it’s just sound that’s space to detach or allows for greater emotional feeling. That’s why humans seek out sound and music, so you can connect with an emotion that the physical can’t quite do justice to.And a big part of my practice is that I really love collaborating, with you, with my friend Danny [Pagarini]; there’s a conversation and communication happening between two people and then that becomes a conversation with the audience, especially in live and performed works. There’s a backwards and forwards that can happen. Danny and I perform improvised sound, so we’re constantly working back and forth between the two of us, but also working with what the audience is responding to and reacting to, and how that becomes this incredibly imperfect but really exciting space, where the audience wills on the music and the music wills on the audience. |

|

Lu:

|

Sound, voice, music; how do you acknowledge these? |

|

Isabelle:

|

Terminology wise? For me, sound is the greater blanket term, voice or voicing for me is that which pertains to the individual — it doesn’t always have to — and when I think about voice it’s one, it’s emanating from me or from a singular instrument, or a singular source. And music feels more structured, sound allowing more de-structuring to happen. It encompasses all of the terms which for a long time don’t fall into traditional Western standards of music. Between utterance, breath. But then that’s also part of music! They’re all interchangeable, I can’t determine them [laughs]. |

|

Lu:

|

Can we come back to this idea of intimacy, sensuality, coming together — your practice is evolving lately to intwine with the tradition of theatre and opera, but perhaps with a more contemporary, queer sensibility and more tactile modes of working? |

|

Isabelle:

|

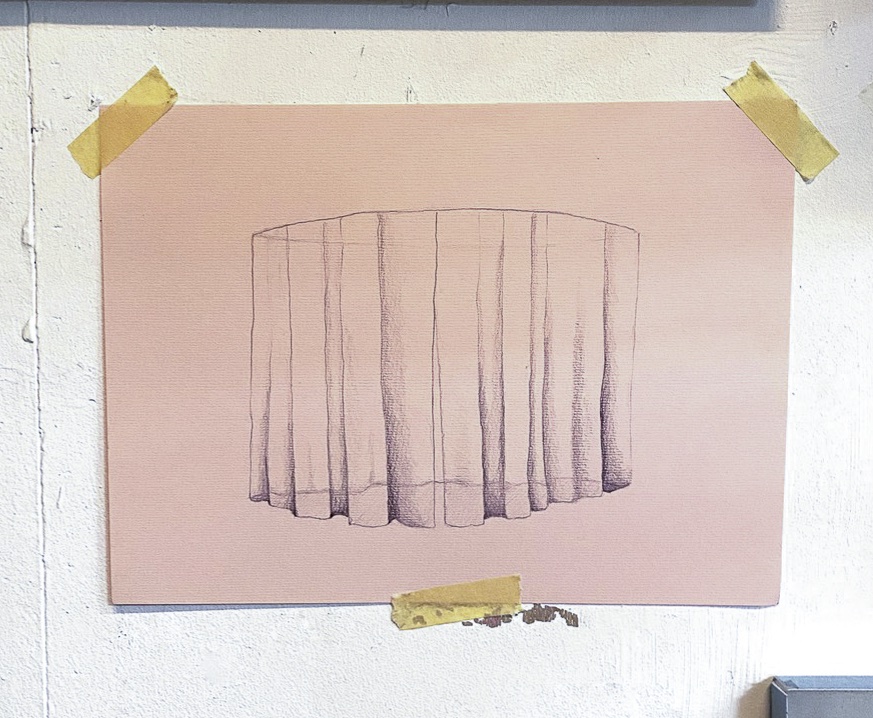

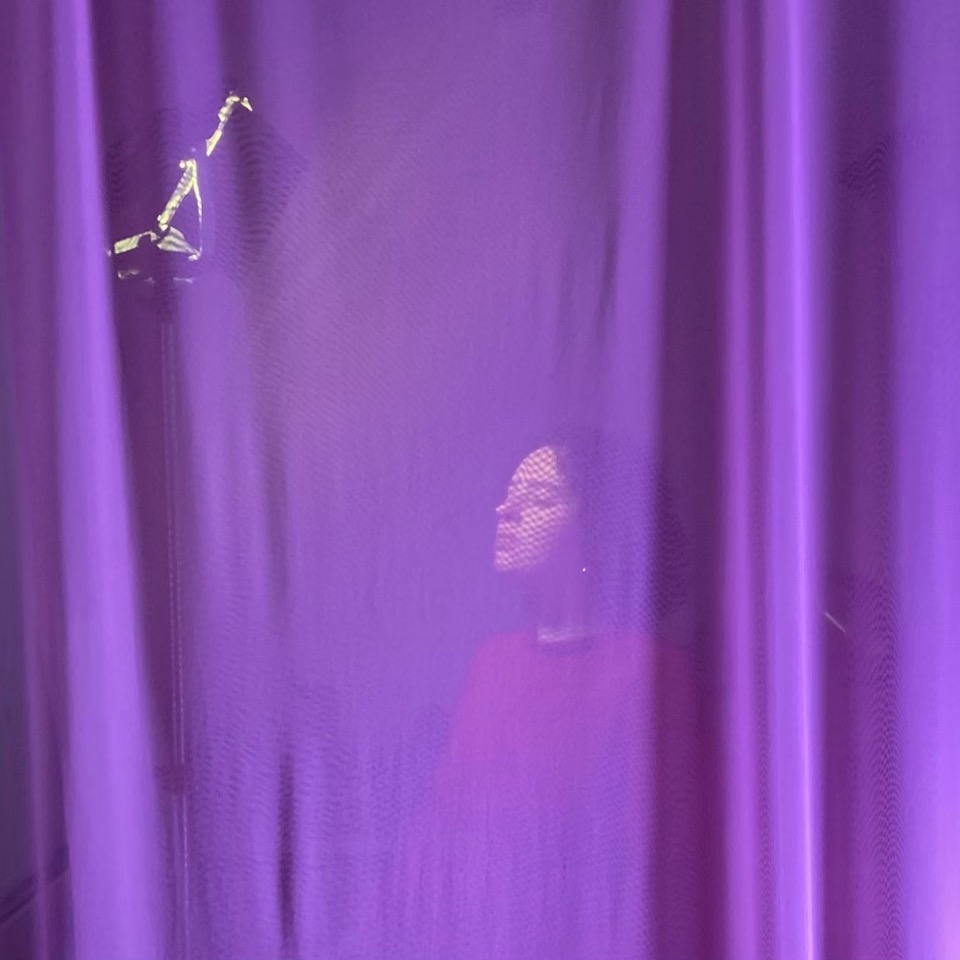

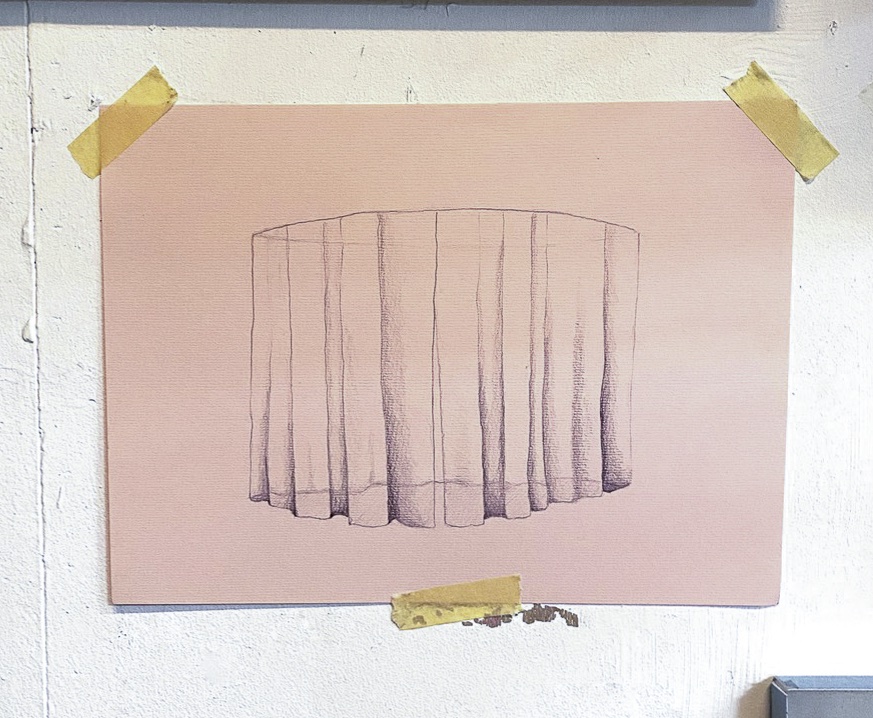

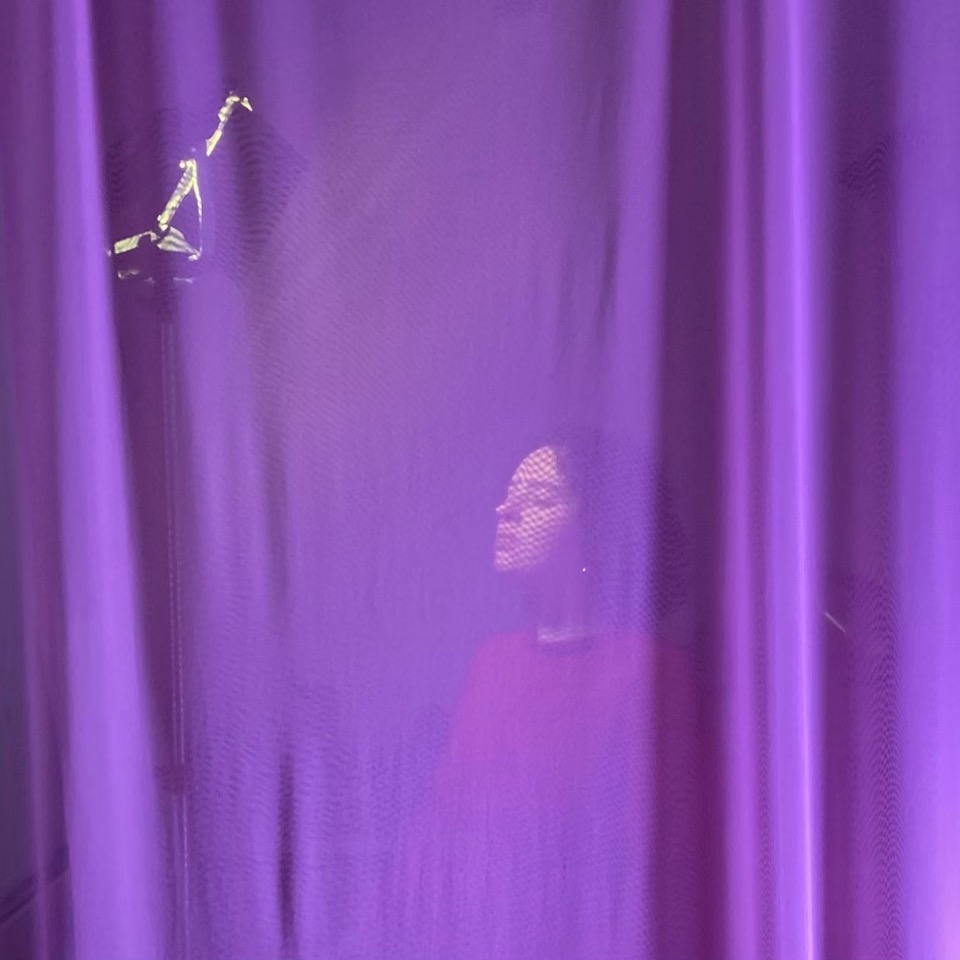

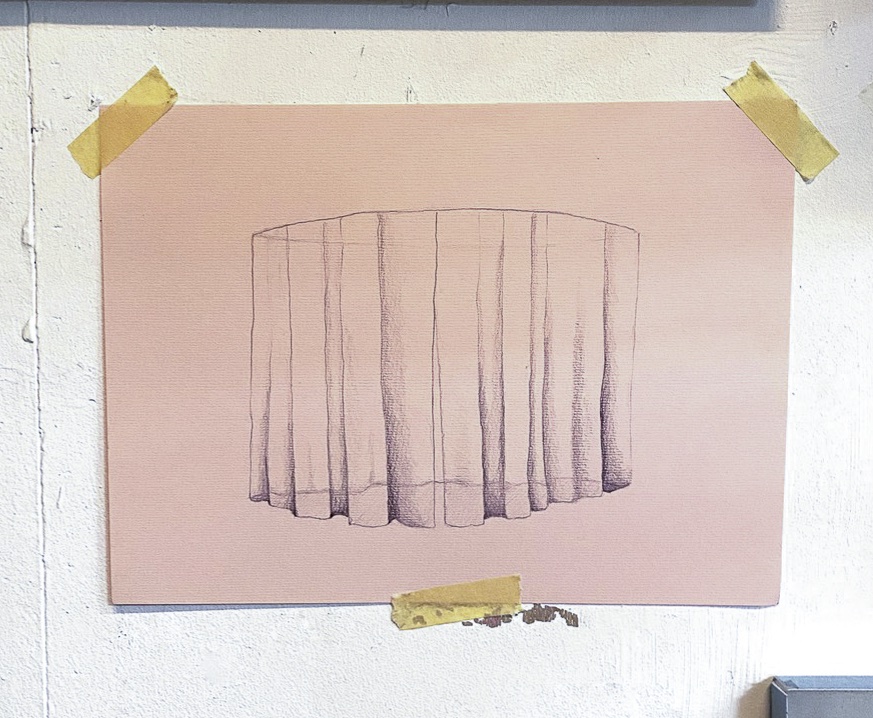

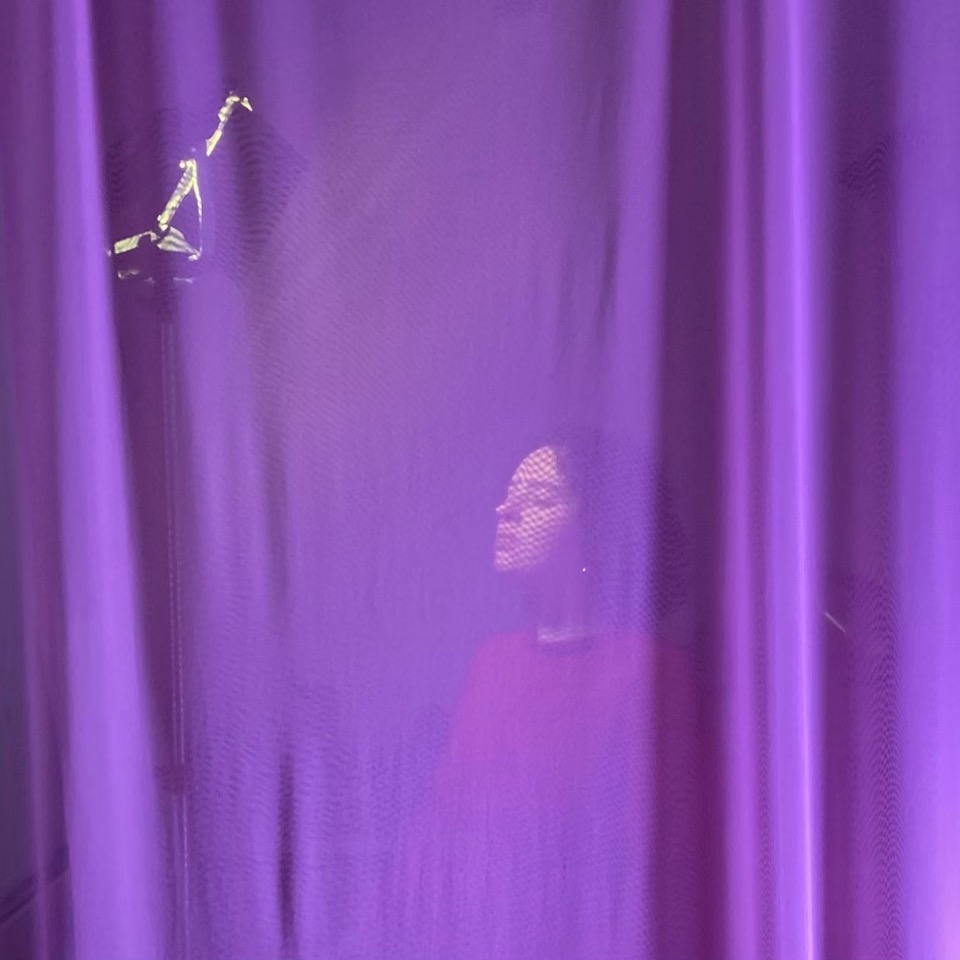

Opera, ballet, oratorio, they’ve really defined a certain perspective of art, and I’m really interested in decoding them and de-constructing them, and understanding why I adore opera and adore drag. In my mind these two art forms are so heavily interlinked; they’re all about excess and a heightened emotionality. They pertain to these totally unattainable versions of the feminine, the masculine, and the divine, and you have voice which follows that. You have the beautiful bel canto soprano who sings the most high gorgeous notes, and you have the deep bass who is the evil figure, he sings so deeply and then the prostrate lover with a tenor voice, and there’s so much campness within that. And with the production of theatre, it’s all about this fantasy of love and death, desire and envy. They’ve always been queer spaces. The theatre has always been a space of solace and expression, and I think a place where a straight patriarchal society comes to release itself in the ecstasy of it all, something taboo is allowed to be totally high art and therefore it can be acceptable in some way. In my practice I’ve really liked taking these stereotypes or quite simple ideas of the spotlight or the curtain, the veil, these spaces which allow for magic to happen and transformation, and thinking about what goes on behind them. Thinking about the fakery, the falsity, that happens to make this grand performance.I did a performance recently at Des Bains [gallery in London] where I quite simply sang in front of a candle which is an ancient singing method for sopranos to show breath control. You should be able to hold your breath so well in your diaphragm and in your lungs that when you sing this really powerful line, you sing it with such power that people at the back can hear you but you don’t blow out the candle in front of you. I’m still learning this, so I continuously blow out the candle over and over again, and eventually I sing a version of Casta Diva - Chaste Diva -, my own version, where finally after a ten minute performance I can sing it without blowing out the candle. But you’re watching me fail constantly, you’re witnessing the fragility and imperfection of my voice. |

|

Lu:

|

Thinking about failure, and what you said about decoding and deconstructing, maybe it’s also opening up and expanding on this idea of it being a very physical and human mode, one open to slippage, but also transcending? Suspending disbelief. |

|

Isabelle:

|

To go back to the audience, to that moment when everyone is on your side, I think that’s really interesting. That suspension of disbelief where you can hold an audience and they forget what is going on around them in order to be solely focused on this one thing, even though it’s completely fabricated and evidently so, but you still feel real emotions. |

|

Lu:

|

I really enjoy this notion of suspending disbelief, and also a willingness to follow misdirection and unfamiliar acts of singing and movement. I’m thinking now about Meredith Monk, an American composer, performer, director, vocalist, filmmaker, choreographer and dancer, who has informed both of our approaches to making and performing — for me writing too — and whom I know we both love! I know she has really opened up your point of reference for what a sounding body can be. Do you want to talk about her in relation to your work? |

|

Isabelle:

|

Yes, she really has. Meredith, as an interdisciplinary practitioner, talks about weaving, having these many strands and drawing them together. It took me a long time to figure out where my work sat, because I didn’t understand that my work could sit in the grey area, in this in-between. Once I found it there, everything came into place when I realised I was somewhere in-between theatrical, music, composer, operatic, fine artist, painter, sculptor. I’m a maker, and that sits in the centre of all of these things. Monk talks about working in between the cracks, which is a really nice way of expressing how her work effortlessly seeps between all of these disciplines.She also set the bar for this practice called Extended Vocal Technique, which is what I follow or use, where you’re taking into account in the voice all of these different histories of singing, vocalisation and traditions. You’re not going by a standard Western metric, you’re thinking about tone and inter-tones, polyphony and utterance, and plosive and exploring every heightened, different voice that the body has, rather than just thinking about this ‘one’ voice. In Bonnie Marranca’s essay, Performance as a Form of Knowledge, they talk about making a sound as both ancient and contemporary, and that’s what I really like about Monk’s practice, it’s often non-verbal and is often based on sound but conveys this captive, raw, emotional power. It’s pure communication. I’m a fangirl for Meredith Monk (laughs), she’s incredible in this way of not just being a performer but someone who’s always thinking about the whole — film, sculpture, props, costume. Effortless and meticulous in the full vision of her work, and her world. She’s creating a world rather than creating individual artworks, which is amazing. |

|

Lu:

|

For sure, I see the threads between you two, these intricacies when thinking about the whole, the theatrics, the wider potential of voice. And off that, what’s happening now, in your studio, in your mind? |

|

Isabelle:

|

In my mind, I’d like to get back from planning mode to the practical. I’ve got a lot of plans for sculptural work, which I think feel like the natural next step, for performances as well. These things bounce back and inform one another [sculpture and performance], so I’d really like to make some more metal works, which allow an extension of the sounding body — so they become sculptures in their own right but are performance objects which can be interacted with. I think for a while I’ve also considered consolidating the sonic work into something bigger, gather these performed works and feel out a narrative, a greater body of work that encompasses everything I’ve made to date. |

|

Lu:

|

I love the term performance object and I’m thinking about scores — scores as performance objects? Surfaces to read— |

|

Isabelle:

|

—Yes! There are so many people who have done exciting things with scores — I did a performance last year with experimental choir Musarc, who I perform with, where the score became performance material. It was an instructional score which then became the ephemera with which the sound was made; you were instructed by the score to rip up the paper, scrunch it, or move the paper, or let it fall. This slowly built into a sonic texture which then became the work, and I loved that piece, it opened up the potential of text-sound relationships. |

|